- Small

- Medium

- Large

Transforming Human History is a campaign to encourage engagement and inspire confidence that change is possible in three areas that will determine the future of life on our planet: nuclear weapons abolition, education for all and climate action. These issues are the focus of SGI President Daisaku Ikeda’s 2022 peace proposal.

Here you can hear from people who are helping to create change.

#TransformingHumanHistory

Because of humanity’s failure to act, the climate crisis has intensified, as scientists predicted it would. The damage to natural systems is undermining the very foundations of life on our planet, placing the future in jeopardy. The crisis can seem overwhelming. But when we take the time to learn the facts and deepen our awareness, we discover pathways of action. Through action we become empowered, and hope is born.

“Learn . . . Reflect . . . Empower.”—Daisaku Ikeda

Expert Perspective

Vanessa Nakate: No Action is Too Small

Climate activist Vanessa Nakate from Uganda was the first in her country to organize a school strike calling for action on the climate crisis. She has been sharing her voice on the international stage, and in 2021, she spoke at COP26. The following is from her April 2022 interview with the Seikyo Shimbun, Soka Gakkai’s daily newspaper.

Three years ago, you went on your first climate strike. What motivated you?

In 2018, I started researching some of the challenges that the people in my community are facing, and that’s when I learned that climate change was one of them. We learned about climate change in school—all I knew about it was that it was causing changes in weather patterns over a long period of time . . .

Three years ago, you went on your first climate strike. What motivated you?

In 2018, I started researching some of the challenges that the people in my community are facing, and that’s when I learned that climate change was one of them. We learned about climate change in school—all I knew about it was that it was causing changes in weather patterns over a long period of time.

I didn’t know that it was actually a great threat facing so many people’s lives right now. I wanted to understand the causes of climate change and its impact on communities, people’s lives and nations at large. I realized that I had already seen some of these impacts in my country: extreme flooding, landslides and drought. I decided to do something about it. Inspired by Greta Thunberg’s climate strikes, I also started striking every Friday. My very first strike was in January 2019 at a local market, and it’s been over three years now.

What are some of the challenges and risks you and others faced going on strike?

Doing climate strikes in my country, and probably in other African countries, is not the same as in Europe or in the United States, where we see large numbers of people coming out and striking. It’s very different for us. In the beginning, I would do these strikes by myself or with a friend, and we would go to the streets with our placards.

The first global climate strike must have been in March 2019. In the global climate strikes, people organize with many others, but I couldn’t do that. I didn’t have the resources to do that, I didn’t have the permission to do that. What I did was go to the principal of a local school and request permission to speak to the students at that school and do a climate strike with them. That was the start of me reaching out to schools.

Education is really respected in our communities, and many parents work so hard to make sure that children go to school, stay in school and also finish school. This makes it so hard for students to walk out of school, because you could be suspended or expelled. This is why I got permission to go to schools to talk to students about climate change.

It’s not easy to get permits or the resources to organize huge climate strikes. I remember my first and last climate strike at the Parliament of Uganda. I did that strike with my friend Elton, and we had to explain to the authorities that our strike wasn’t for political purposes because the word “strike” on our placard was disturbing to the authorities. The next time I tried to do a strike at the parliament, I was refused from doing so, due to fear that I would bring public attention or cause unrest.

Some of my friends and fellow activists have been arrested for striking in front of the parliament. These are some of the challenges that we’ve seen.

Addressing Energy Poverty in Rural Schools

In 2019, you launched the Vash green school project. Please tell us about this.

I started this project in 2019 to address energy poverty in rural schools by coming up with economic and sustainable solutions. It involves the installation of solar panels and eco-friendly stoves in schools in Uganda. This was to help communities and schools transition to renewable energy, because not every school can afford it, not every family or community can access it. Through this project that is supported by people in different parts of the world, we install solar panels for free at schools to help drive that transition. Most of the schools in Uganda use firewood for the preparation of food. This means the cutting down of trees. The eco-friendly stoves do not completely eliminate the use of firewood, but they help reduce the amount of firewood used to prepare food.

We construct the eco-friendly stoves at the school. In addition to reducing firewood, they also reduce indoor air pollution for the chefs. This project has also been a way for us to extend climate education to schools, teachers and parents. We engage with the community.

It has given us an opportunity to speak to students about climate issues and the climate work that we do. We are able to show them the power of small actions—their actions—and the power of their voices in transforming the world. To date, we’ve done installations in 13 schools.

What kind of changes in behavior and attitude have you seen in those children and families?

We return to schools for feedback. The stoves greatly reduce pollution in the kitchens and students are also able to study for longer because they have electricity, thanks to the solar panels. When in rains, the classrooms can get dark, and it can be hard to read. These improvements have led to an increase in student enrollment.

“Save Congo Rainforests”

You also make a strong appeal for the protection of the rainforests in the Congo Basin, which borders Uganda. Can you tell us more about this?

In 2019, I did a presentation at one of the Rotary Clubs in Kampala. After my presentation, a couple of questions were asked. One of the questions was why the world was not paying attention to what was happening in the Congo Rainforest. At that time, I didn’t know much about it. I started to read and educate myself about what was happening in the Congo Rainforest and learned about the ongoing illegal logging, road construction and mining of mineral resources. I remember one article stating that the current destruction in the Congo Rainforest could mean the complete loss of the forest by 2100. To think that this is the second largest rainforest in the world and there is not much information about it was surprising.

There are endangered species within the forest, such as the okapi (a member of the giraffe family). The only home for the okapi is the Congo Rainforest. Additionally, over 75 million people depend on the existence of this forest, and it is home to thousands of species of birds and animals and plants. I realized that I had to start speaking about it.

I started to do my own strikes, mainly from home. I would make a placard with the words “Save Congo Rainforest,” for example, and would share this on social media. I just kept sharing and sharing, and I remember on the 15th day of striking, Greta Thunberg retweeted my tweet about the Congo Rainforest. As a result, many people started to get more engaged and started organizing and sharing pictures of the rainforest. I learned that some people didn’t know about the existence of the rainforest, let alone the destruction taking place in it. It’s actually possible for an entire ecosystem to disappear without people knowing about its existence.

Climate Crisis Impact in Africa

At the Davos Forum in January 2020, AP Press cropped you out of a photo of the young climate activists. Your response was really powerful. You said, “You did not just erase a photo. You erased a continent.” Could you talk more about this incident?

When I first saw the picture that was posted, I was really frustrated and heartbroken. One of the things that I really emphasized at the press conference was the importance of listening to activists, especially from the areas most affected by climate change. So, to find myself not in the picture or not in the article was really frustrating and disappointing.

Africa as a continent is responsible for less than 4 percent of global emissions. However, we are seeing how many Africans are suffering some of the most brutal impacts of the climate crisis. This year, we’ve seen the drought in eastern Africa that left over 26 million people with no access to food, with no access to water. We’ve seen the impact of Tropical Storm Ana in southern Africa that led to many deaths and thousands of people being displaced, in addition to farms, businesses and homes being washed away by flooding due to heavy rainfall.

The climate crisis is evident on the African continent. We are already fighting for survival at 1.2 degrees above our average temperature, not to mention the predicted 1.5 degrees global increase, and it’s already caused much destruction for so many communities in Africa. There are so many communities that end up being marginalized, whose voices first of all are not being listened to, whose stories and experiences are not being amplified, and yet, these communities are suffering so much.

The climate crisis will eventually affect all of us if we don’t do something about it. You may not be there to see the effects, but it could affect your children and grandchildren.

The earlier people understand that it is a human responsibility, the easier it will be for us to take action and build a future that is sustainable and equitable and healthy for all of us. It’s not about you, it’s about everyone. Seeing your neighbor being happy, seeing the child next door being able to access food or finish school, these are the real joys of life. It’s about having a world that’s safe and healthy for everyone.

A Climate Solution: Educating Girls

You also really emphasized that the education of girls is a crucial way to address the climate crisis. Could you tell us more about this?

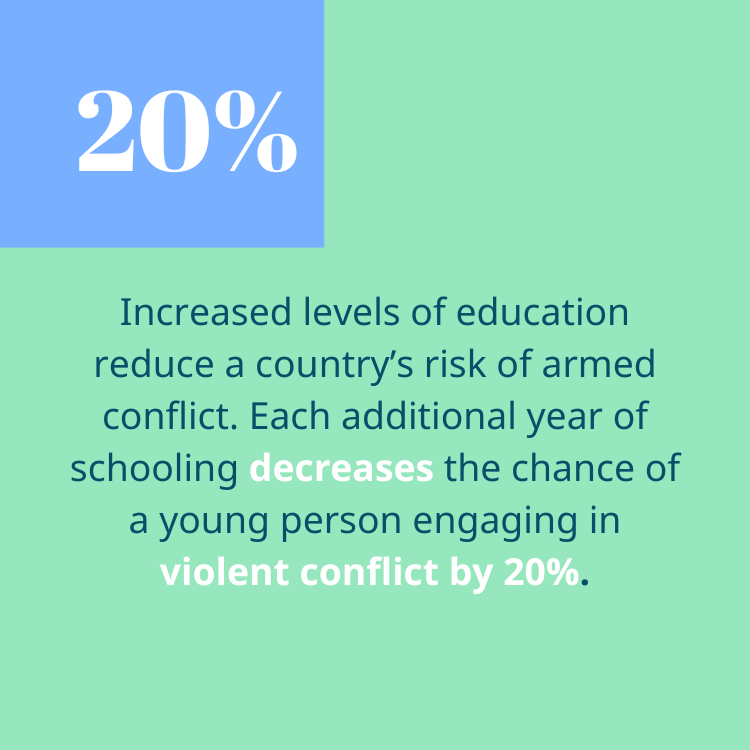

When it comes to climate solutions, we always hear people talk about things like solar power, green spaces and electric vehicles, but you never hear about girls’ education being a climate solution, and a powerful climate solution at that. Project Drawdown lists a hundred things that we can do to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and ranked number five of the most impactful solutions is educating girls and family planning.

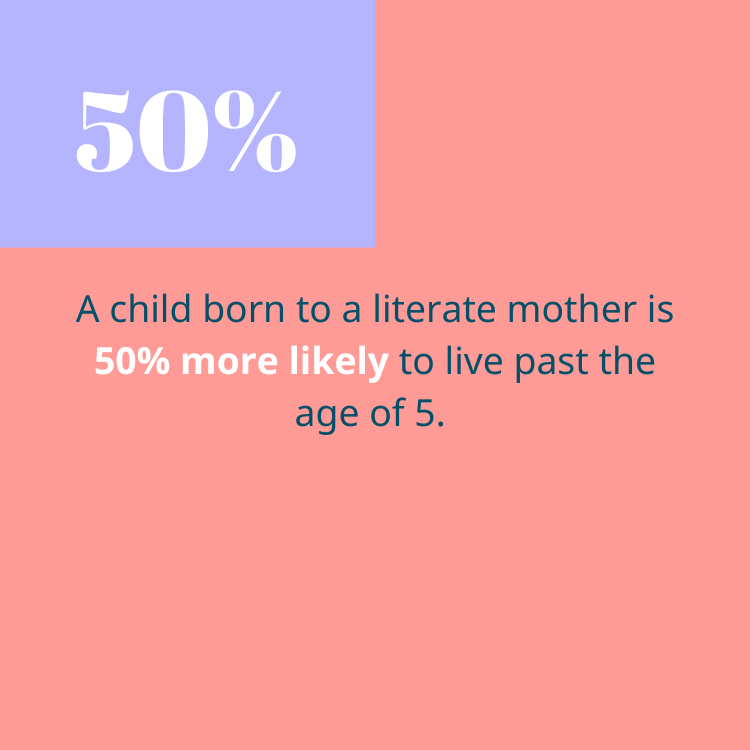

Women’s empowerment and educating girls not only benefits the individual, the effects cascade through the family and community and world at large.

This is also a solution that will reduce already existing inequalities that so many women and girls face as the climate crisis escalates. In many communities, women and girls are on the frontlines of the climate crisis, because they have the responsibility to provide food and water for their families, especially in rural areas. They are the ones who have to walk long distances to collect water for their families. If the family can’t take care of their children anymore, some of their children are forced to drop out of school, and again, it’s always the girls who are forced to drop out of school. Many are forced into early marriages.

Educating and empowering women and girls will help reduce many of these inequalities; it will build the resilience of women and girls, and also reduce greenhouse gases at the same time.

Inspiring Climate Activism

President Daisaku Ikeda has long called for the 21st century to be “the century of women” and “the century of Africa.” This is based on the Buddhist philosophy that those who have suffered the most have the right to be the happiest. In 2005, he met with the environmental activist Dr. Wangari Maathai, to discuss the power of women and other issues.

I greatly applaud the work of Wangari Maathai. I wish we learned more about such women and their incredible work in school. Wangari is an inspiration for me. I believe she set a great path for all of us, and there is so much to learn from her.

In 2019, we started a small group called Youth For Future Africa which later turned into the Rise up Movement. In the Rise Up Movement, the first thing we do is the climate strike—organizing and mobilizing climate strikes within different parts of the country: bringing together as many young people as possible, meeting them in schools to do the strikes, organizing workshops and skills development for all of us as activists to learn how to do our activism better and how to talk about some of the issues that are affecting our lives and communities.

We also have a number of projects within the Rise Up Movement. I spoke about the Vash green school project. We also have a tree planting project called +1Tree Project that is led by Evelyn Acham. We plant fruit trees and give fruit trees to different households. We also have a project called Girl On The Move Initiative led by Isaac Ssentumbwe. This project is a skills development project to help equip girls and women in rural areas with skills that they need to become self-employed or apply and look for jobs. We believe that, in the climate justice world, we need more women to be able to access funds to access income so that they can build more climate-friendly homes for themselves and have more climate-friendly futures for their children.

The Rise Up Movement works to ensure that every voice is listened to and every face seen. We really work to ensure that every activist, regardless of how long they’ve been in the movement, is given a platform.

In your book A Bigger Picture: My Fight to Bring a New African Voice to the Climate Crisis, you suggest 10 ways to change society. What particular message would you like to impart to the young people, especially in the Global North?

I think many times, young people will ask themselves what they can do in the movement. I think that question alone is one step toward doing something. I always say to find a group that is already organizing in your community; you don’t have to start alone. But, if you don’t see any community that is organizing in your country and you want to organize, then my advice is for you to start. You don’t need many resources; all you need is a placard and a marker to write that message and share it on your social media. That is what I did, and that always reminds me that no action is too small to make a difference, and no voice is too small to make a difference.

I think it’s important for young people to know that there is so much power in their voices and that their voices are actually transforming the world. There is so much power in their actions that is already transforming so many people’s lives. We may not be able to do things on a global scale, but we have seen the changes on a local level—the joy, the happiness in people’s faces when you bring these projects into their communities.

Whatever you do—if it’s doing that small project in your community, speaking to your family or friends—that is something that you are doing for the environment, for the planet, for the people. No action is too small to transform the world.

A Buddhist Response to the Climate Crisis

Robert Harrap, SGI-UK General Director

Creating a Carbon-Neutral University

Philip Arvind Franck, Germany

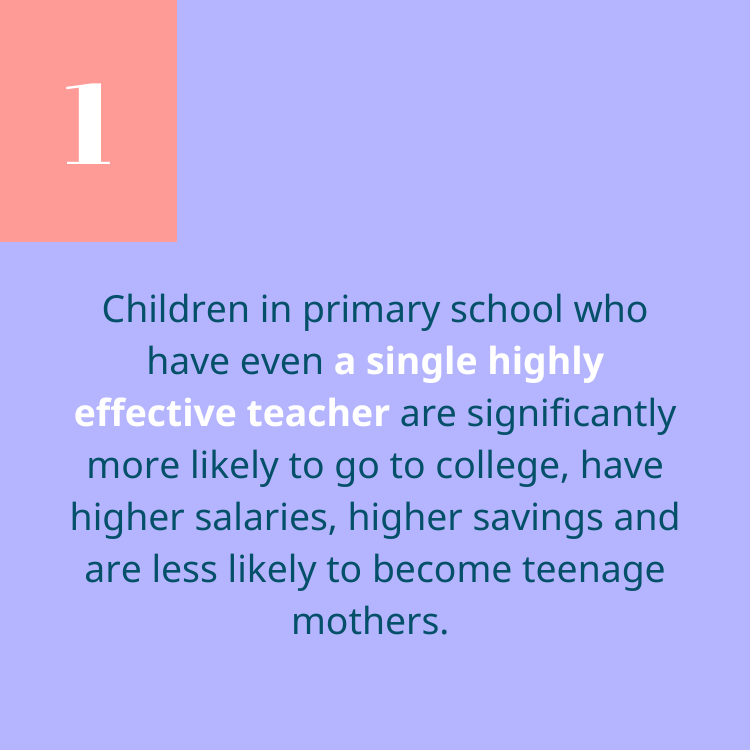

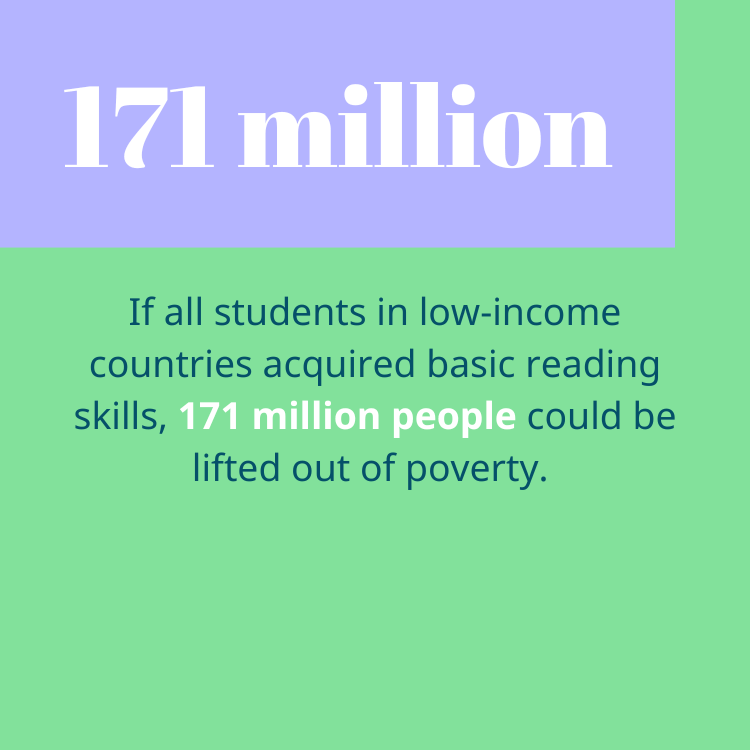

”Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world,” said Nelson Mandela. The world is in desperate need of change. Access to education changes lives. It leads to a reduction in poverty and violence and increases equality and opportunity. It transforms communities and empowers us to move society in a positive direction.

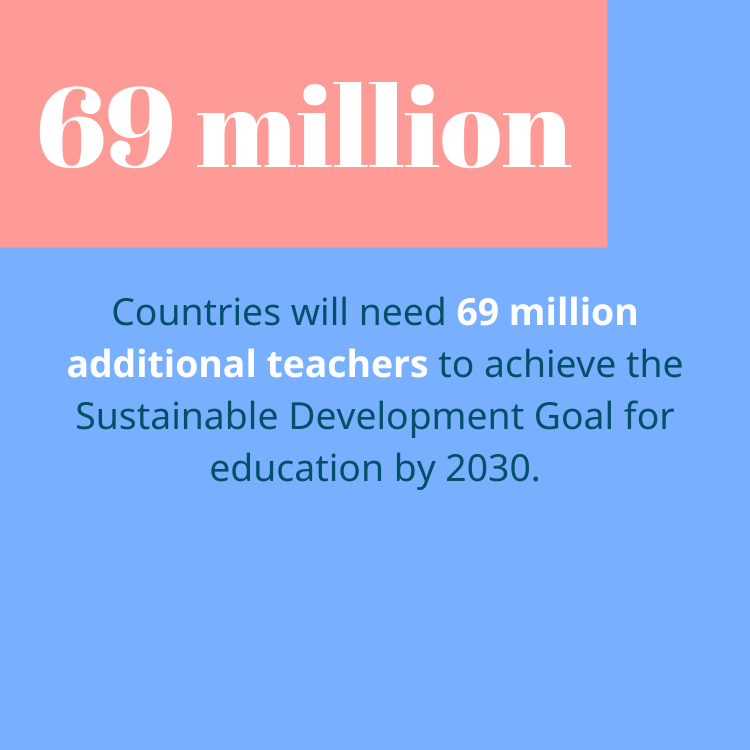

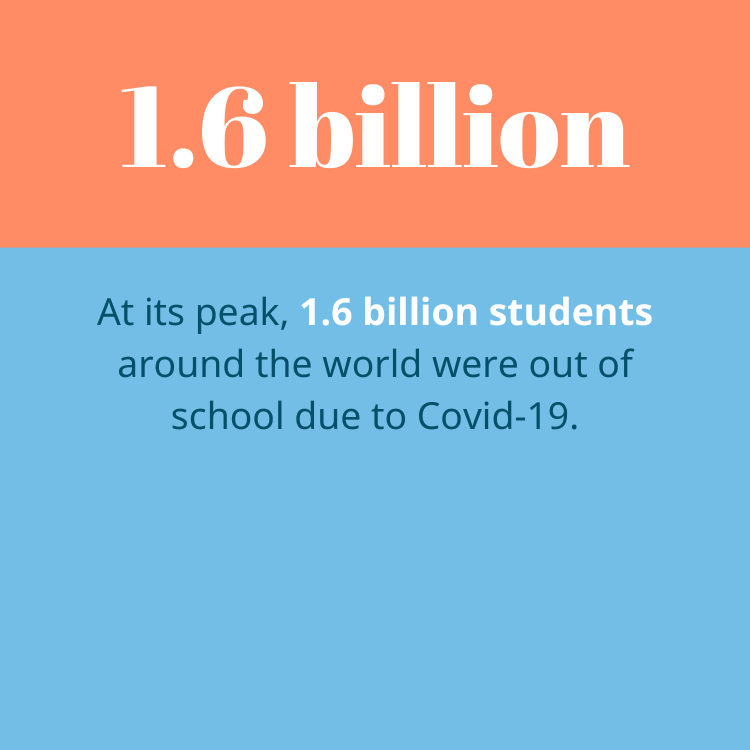

The United Nations has estimated that COVID-19 has wiped out 20 years of education gains. And around the world, education is under threat. Expanding access to education means securing the future of humanity on this planet.

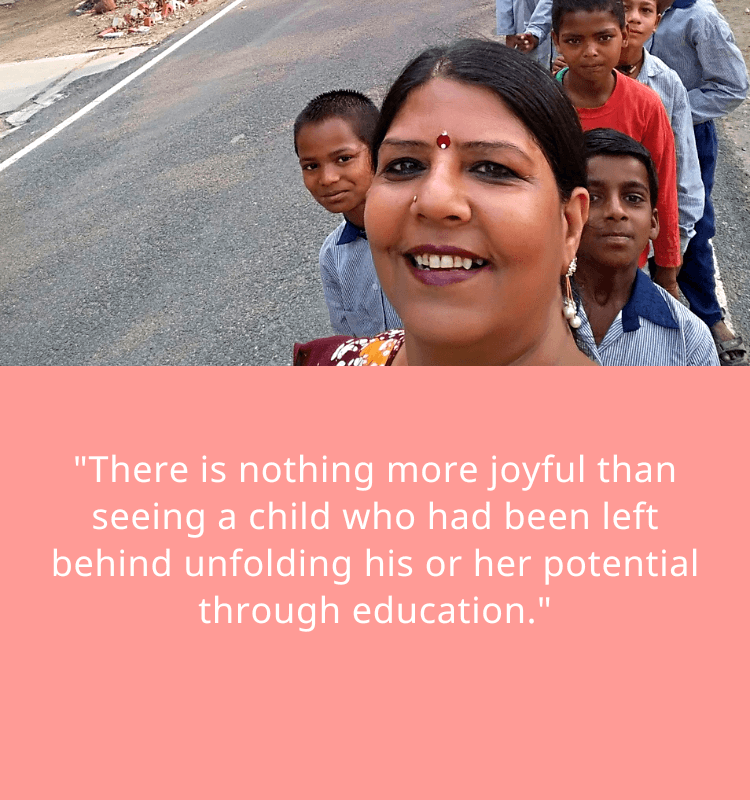

From Insult to Honor: Becoming a Force for Transformation

Arunima Sharma, India

From Trauma to Drama

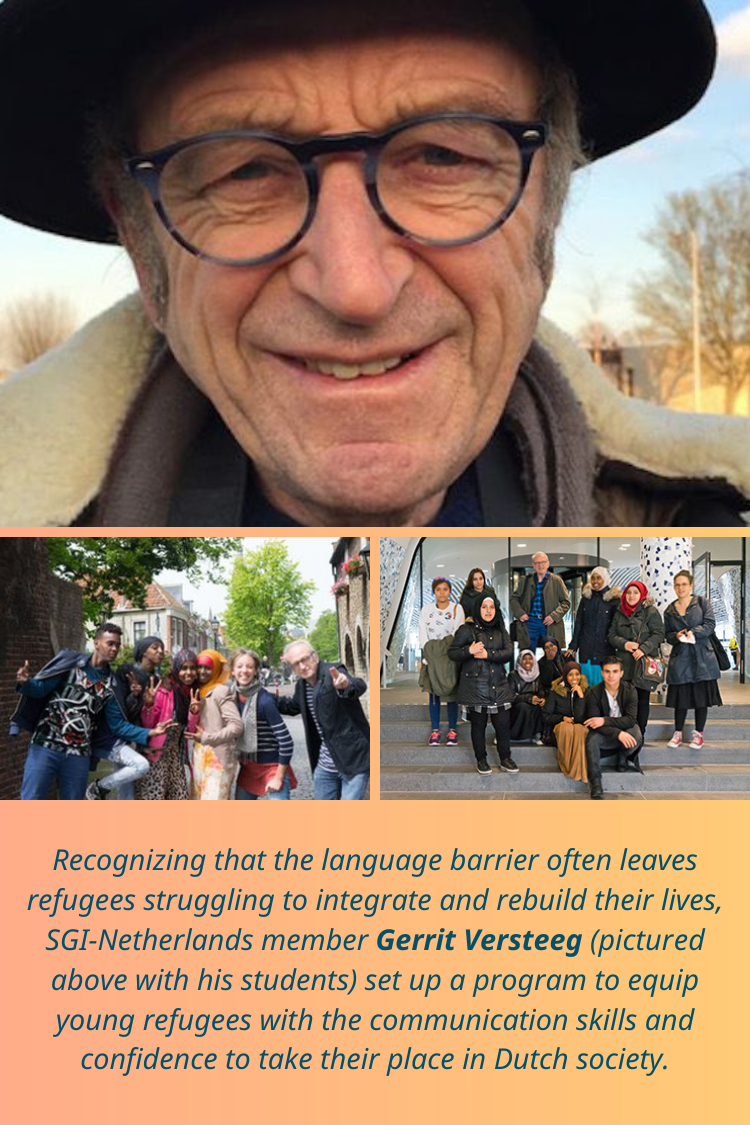

Gerrit Versteeg, Netherlands

How did you begin working with refugees?

With more refugees entering the Netherlands, especially Delft, the city I am from, there has been an increase in the number of refugee youths who have missed many years of education because of war in their home countries. About a decade ago, Dutch education authorities began providing special classes to help close this gap. However, these classes have not always been sufficient, and students have continued to struggle with confidence and self-expression. Their often terrible experiences in war zones impact their ability to absorb new information—their minds are still full of war . . .

How did you begin working with refugees?

With more refugees entering the Netherlands, especially Delft, the city I am from, there has been an increase in the number of refugee youths who have missed many years of education because of war in their home countries. About a decade ago, Dutch education authorities began providing special classes to help close this gap. However, these classes have not always been sufficient, and students have continued to struggle with confidence and self-expression. Their often terrible experiences in war zones impact their ability to absorb new information—their minds are still full of war.

Some years ago, together with Jeroen van der Zijde, who took the initiative, and a social worker, we started a special class to provide additional language lessons to refugees, coupled with social empowerment lessons.

What kind of challenges do refugees such as the students you teach face in Dutch society and in learning Dutch?

The biggest problem is the lack of oral communication skills owing to a lack of contact with local peers. For example, one student who had already spent several years in the Netherlands mentioned to me that his greatest wish was to have a Dutch friend. He is not an exception. How very sad.

Students themselves often stay within their own ethnic, national or religious circles for security, which compounds their sense of exclusion from mainstream Dutch society. Because of this feeling of exclusion, some have ended up leaving the country to take part in the war in Syria and Iraq. The sad reality is that a sizable proportion of those who leave the Netherlands to do this have come from Delft.

You began incorporating drama into language teaching. What was the idea behind this, and what were the initial results?

At the end of the first year of our special class, in 2014, the students’ vocabulary had significantly improved, but their communication skills were still very poor. We decided in the second year to give more attention to this, and to this end, a drama teacher was appointed. That led to a clear improvement in students’ self-confidence and ability to express themselves, but their language fluency remained below the desired level.

In 2016, we decided to focus on enabling the students to tell their own stories. We called this the “Language Theater,” with a clear focus on teaching language through drama lessons.

Initially, it was chaotic. The backgrounds, ages and educational levels of the students were too diverse. We had Somali, Eritrean and Syrian boys and girls between the ages of 14 and 18, ranging from nearly illiterate to highly educated. This led to conflict and bullying between groups of students, including physical threats outside the classroom. The effects of war were clearly apparent in their lives.

How did this whole experience challenge you personally, and how did you use your Buddhist practice to confront that challenge?

I became extremely sensitive to any sign of aggression, to the point that it sometimes interfered with my performance as a teacher—I would physically tremble and find it difficult to speak. Through chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, I realized first of all that I had to accept their war zone condition as a fact, gain courage and deal with it. Then I realized that despite our different backgrounds and religions, we could still create real heart-to-heart connections with each other and share our lives.

We encouraged dialogue and mixed the groups so that students from different backgrounds would have to work together. Initially, this was difficult because the groups offered a kind of safety. One student, for example, refused to join a mixed group. We discovered she had fled her country after she had lost both parents. Instead of insisting, we gave her time to make her own choice, and gradually she was able to take part in the mixed group. This incident taught us to pay attention to the personal situation of each student.

What results did the Language Theater yield?

In the Language Theater, attention was given to each student to enable them to tell their own story. Each student’s story strengthened solidarity among the students, as each began to look beyond their own group and see themselves as part of the larger community with common needs and interests.

In line with our principle of “put the school in the society and the society in the school,” halfway through the year parents, municipal administrators and role models from the ethnic communities—for example, a successful Somali entrepreneur and a young Syrian woman who works for UNHCR—were invited to the school.

During the meeting, the students voiced their own perspectives, and it became clear that parents often have quite rigid expectations of their children or limited views of their possibilities. Typically, they want their children to become doctors, teachers, police officers or soccer players.

We then invited representatives of several professions—doctors, leaders of a childcare center, a police officer and a municipal administrator—to be interviewed and filmed by the students.

At the end of the 2016–17 school year, the students presented a play that they themselves had written and for which they had chosen their own roles. It was attended by their family members, the school management and the councillor for education of the city of Delft. Prior to the play, each student presented a monologue in which they shared their own story or wish for the future.

The result of this process was that the students gained self-confidence in Dutch society and a strong sense of their own unique mission. And, of course, their parents were very proud.

How are things now?

The project created positive connections and understanding between students and between the different ethnic groups, as well as between the students and teachers, parents and authorities. By the end of the 2016–17 school year, they had significantly more respect for diversity and a lot more confidence that personal or group problems can be solved through dialogue.

It was also clear that it had enhanced the students’ autonomy, as seen in the way they turned their own stories into a play and chose their own roles. The project generated a great deal of happiness among the students and led to improvements in their personal lives. Many were able to successfully progress on to higher education.

A local paper ran a front-page story on the Language Theater, with a picture of the mayor of Delft surrounded by the students. Within the municipality of Delft there is now a growing awareness of the importance of these initiatives.

Educating for Happiness: The SGI-Panama Educators Division

Heidy Saucedo, SGI-Panama Educators Division Head

Everything you treasure could be reduced to ashes in a moment. There is more danger of a nuclear weapon being used now—whether deliberately or by accident—than at any time since the Cold War. So long as these indiscriminate weapons of mass destruction exist, humanity lives under the constant threat of annihilation.

At the same time, through the momentum created by countless concerned individuals around the world, nuclear weapons have now been outlawed by the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which came into force in 2021. So far, 86 nations have signed the treaty. This does not yet include any of the nuclear-armed states. This generation can be the generation that finally rids the world of these inhumane weapons.

Find out how the numbers below are related to nuclear weapons by clicking on the images.

Expert Perspective

Doing What We Can: A Conversation with Beatrice Fihn

Youth Voices for a Nuclear- Weapon-Free World

Soka Gakkai Youth representatives who attended the historic First Meeting of States Parties (1MSP) to the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), held in Vienna, Austria, in June 2022 share their convictions.

Dignity, Security and a World Free of Nuclear Weapons

Anna Ikeda, SGI Office for UN Affairs

Includes playlists on Buddhist practice for beginners, members' stories from around the world and Soka Gakkai activities for peace