Making Resistance My Ally

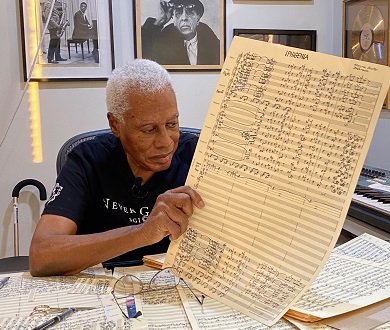

Wayne Shorter, legendary American jazz saxophonist, composer and longtime Soka Gakkai member, has earned worldwide recognition for his mastery of the saxophone, including six honorary doctorates and 11 Grammy Awards. The New York Times named him the foremost living composer in jazz. At age 88, together with five-time Grammy award winner Esperanza Spalding, he completed his first opera, Iphigenia, which he views as a continuation, not a culmination, of his life’s work.

Here Mr. Shorter talks about the creation of Iphigenia and how Buddhism helps him break through deadlock and welcome life’s challenges with the spirit of “Bring it on!”

Can you share with us how the idea for Iphigenia came to fruition?

I started experimenting with writing music when I was in high school. Before I was drafted into the US Army, I was working on an opera called The Singing Lesson. I continued to write things down in a little book that I kept with me but never brought it out. Then I started getting auditions with big bands as a saxophonist. I joined Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, and later on, I joined Miles Davis’ band. After that, I formed my own band—Weather Report. As time went on, I kept writing music in my little book.

Through practicing Buddhism, I realized that nothing is wasted. Nothing is thrown away. Everything in my life has something to do with my development on the road to enlightenment. Even if I wasn’t getting record contracts that led me to writing hit songs, I didn’t worry. I just kept going.

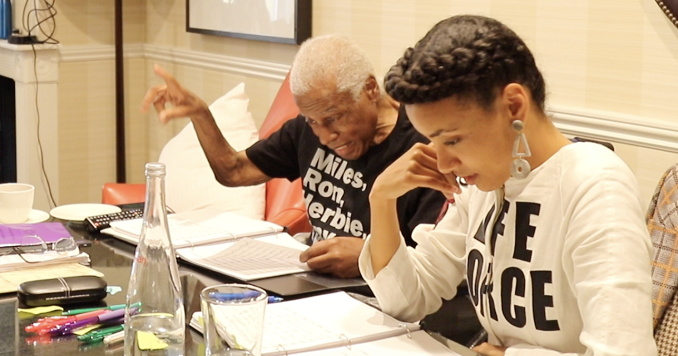

Then I met a young lady named Esperanza Spalding. I thought to myself, “Here is a person that is original.” We met again in Europe doing interviews. As we were talking, she said, “That opera that you started when you were 19, why don’t you continue it?” Buddhism taught me that anything we promise to do, we must follow through with. We must not leave anything undone and have regrets. So, I decided I would work on the opera, and Esperanza took it upon herself to get it funded.

She told me she could do the story—the libretto. Before the pandemic, we worked together in isolation in Portugal. For some time we worked on our pieces separately, not playing, just writing, before hearing what the other was composing. Then the story started to grow.

What challenges did you encounter along the way?

In the midst of working on the opera, I got sick and had to go to the hospital. At one point, I was near death. In that condition, I had strange dreams, but I could see all of my friends in the Soka Gakkai and hear my wife, Carolina, chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. When I woke up, I got back to work.

We had offers to work with opera companies. But we didn’t want someone to shepherd us. Esperanza asked me what I really wanted to do. I told her I wanted to create a company that’s dealing with real magic. We have created a company now that works with incredible creators, producers, conductors, directors and architects.

Iphigenia premiered in Boston in November 2021 at the ArtsEmerson organization. Each night was sold out. They said they had never seen lines go around the block for an opera. Many of the people there to see it were young. No one was worried about wearing a tuxedo. It wasn’t like the old days, when people had their nose stuck in the air, acting all hoity toity.

Is that something you wanted, for Iphigenia to be accessible to all people?

Yes. Many of the old composers back in the day wanted their art to be accessible too. They wished for the general public to come to the opera. Mozart hung out in the streets and wanted his friends to come. Only the aristocracy and wealthy people put a barrier between the art and the general public. I’d like to say to them, “Get off your high horse, open the doors and let me in.” I wanted to break that door down with Iphigenia. There is room for everybody.

You are a world-renowned jazz legend. Do you ever have doubts or hit roadblocks?

I had the honor of being called by Rutgers University in New Jersey, asking if they could name their new music building the Wayne Shorter School of Music. They are building it now. They sent me an honorary doctorate. I have six of them—including from The Juilliard School, New England Conservatory of Music and Berklee College of Music. I have a friend who is watching them break ground on this new building. This encourages me.

I never thought about backtracking because I have my shirt that says, “Never Give Up!” In the hospital, when I couldn’t breathe, I chanted Nam-myoho-renge-kyo at half voice so that I could chant a lot. I could see that all of this chanting pushed me through any thoughts of stopping, giving up or hesitating. It’s more than just being stubborn, obstinate or contrary. It’s deeper than that.

Through practicing Buddhism, I realized that nothing is wasted . . . Everything in my life has something to do with my development on the road to enlightenment.

I know that this spirit can never be taken away from me, unless I abandon it myself. Nothing outside of me can make me abandon it. I like the phrase from President Daisaku Ikeda, “Faith is—to fear nothing.” That stays in my mind, body and in my fingers. I say, “Onward!” And that’s that.

For young people just starting out with their Buddhist practice and youth too afraid to pursue their dreams, what would you want to say to them?

President Ikeda said somewhere to make demons and devils your allies. The way to do that is to study and put into practice this Buddhist philosophy. To fear nothing is in complete juxtaposition with being fearful of doing something. Fear of what? Fear of the unknown, of being criticized, of being rejected. Fear of being looked at and talked about in ways that you think are demeaning. Fear of your superior, your boss, or people around you, singling you out as crazy or stupid. Fear of your ideas being attacked. The fear of the sound of your own voice when you speak your mind. Fear of being punished. All of that is inbred from the cradle at birth. Sometimes I say, many of us have been hijacked from the cradle. Like the baby turtles who have to make it to the sea. Some of them do, but many of them don’t. We have to make it to the sea of the wisdom of life.

My only determination is to bring to life bonno-soku-bodai (earthly desires are enlightenment). To me, it means to try something and, when you think you can’t go on, renew your life again. And really live. Live with the many dimensions of myoho and renge. I’m Nam-myoho-renge-kyo personified. I’m not playing with it. I’m doing a dance with it, and I make music with it. It is incomparable—the meaning of living it rather than just talking about it. I’m doing the best I can to live it right now. Young people, check out what is written in the writings of Nichiren and President Ikeda.

We heard that you dedicated the opera to President and Mrs. Ikeda.

This opera as well as my album, Emanon. I feel that in all the time that I’ve known President Ikeda, he knows the essence and heart of the creative process. He can simplify something that seems difficult to unravel in life. He knows already what there is to be understood and enjoyed.

What is your definition of success?

It is to run up against so many obstacles that you break through and ask for more obstacles. Like I say: Bring it on. Bring on the resistance. Because I know better. I know that chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is the key to making the resistance my ally.

If you make success your ally, it is all over. You are trapped. You have been fooled. It’s as if you have been in hell for so long you think it’s heaven. I’m not going to be laughing my way through what I call success. I’m not going to be like, “I got what I want.” The success to me is always “earthly desires equal enlightenment.” That is my partner and sidekick.

Some very famous people come to our local Soka Gakkai district meetings. They come to these meetings so that their names can be lifted above the glamour and success and money. They want to be above that so they have to dig deeper into their lives and study this Buddhist philosophy.

I want to continue to study, in fact, I have a lot of reading to do. I want to build on this achievement to achieve more.

Adapted from the January 1, 2022, issue of the World Tribune, SGI-USA