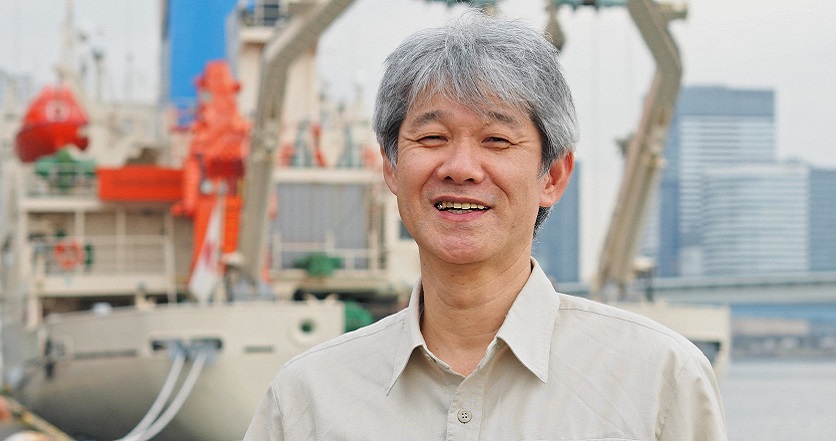

The Art of Living True to Oneself

Award-winning historical painter Yang Binghui from Taiwan shares his journey of becoming an artist and describes how Nichiren Buddhism helped him overcome a series of life-changing obstacles to live true to his heart.

For generations, the men in our family have been short-lived. My great-great-grandfather died at the age of 23 in the Battle of Baguashan, which was fought against the invading Japanese army in 1895. My great-grandfather died in 1907 at age 18 in the Beipu Uprising, when Taiwan was under Japanese rule. Moreover, hepatitis B has been in our family since my grandfather’s generation; my father died from the disease at 47 and my uncle at 51, and I contracted the illness shortly after birth.

My father was a researcher at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Taiwan Malaria Research Institute, and because I was academically gifted, he was resolute that I should become a physician. I didn’t like the way we were made to cram knowledge in at school and preferred to study whatever interested me—biology, painting, martial arts and playing musical instruments. My dream was to become a natural scientist.

At the age of 15, I wanted a microscope to observe insects and plants, but microscopes were too costly for my parents to afford. I then came up with the idea of creating my own microscope and made one successfully. I even won the silver prize for my unique invention at an international invention exhibition in Nuremberg, Germany. Notwithstanding my accomplishments, my father was unhappy with me. In fact, he destroyed my cherished specimens and threw me out of the house.

However, seeing him suffering from illness and financial hardship, I felt I had no alternative but to take the university entrance exam and, in 1980, I entered National Chung Hsing University Department of Chemistry. When I was on leave in my first year of college, my father was diagnosed with liver cancer. He passed away only 11 days after he was informed of this illness. His death was a shock; at the same time, I felt as though I had seen a glimpse of what my future might be.

New Beginning

As I had lost all incentive to continue my studies, I decided to leave university and establish a sales and manufacturing company for the microscope I had invented. Leaving the finances and management, which were not my forte, to my business partners, I focused on the technological and production aspects of our company.

The business was doing well, but as I was in the dark about business management and law, I was cheated out of the profits, and just like that, I was bankrupt! I suddenly found myself not only struggling with my ailment but confronting my karma of suffering financially as well.

I found a ray of hope in Nichiren Buddhism and joined the Soka Gakkai in Taiwan.

It was then that a female friend, who would later become my wife, shared her conviction that I could definitely transform my karma through faith. I found a ray of hope in Nichiren Buddhism and joined the Soka Gakkai in Taiwan in 1983 at the age of 24. What bolstered my decision was learning about the Soka Gakkai’s three founding presidents’ anti-war sentiments and stance on peace.

Soon after, I came up with the idea of starting a science experiment class implementing the pedagogies of John Dewey and first Soka Gakkai president Tsunesaburo Makiguchi who both emphasized the importance of children’s independence and of learning through experience. I rented a small classroom and began with a few desks and chairs. The classes quickly became popular and a stable business was born. Over the course of 29 years, I have taught over 1,000 students, running as many as 10 classes in the most active years.

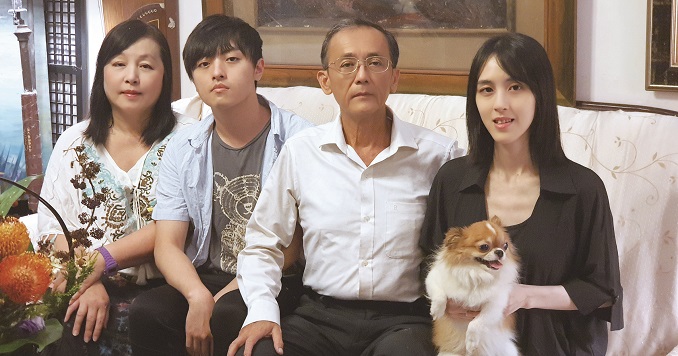

In 1984, I got married, and in 1990 we were very excited to welcome our first daughter into the world. In 1995, we lost our second child two days after birth, due to a blood disorder called Hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN). Though devastated, we roused ourselves from despair with the conviction that there must be a profound meaning to what had happened. My wife and I were appointed leaders in our local Soka Gakkai group and threw ourselves into developing our community.

In 1997, our son was born. And in 2000, the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, which was founded by President Daisaku Ikeda, had a traveling exhibition titled “Masterpieces of Western Paintings from the Renaissance to the 20th Century” that was shown in Taiwan. My wife happened to be a docent for this exhibition. Inspired by the paintings, I decided to start painting. This was a turning point in my life.

Drawing on the Past

I was good at painting flora, but some paintings depicting landscapes of Taiwan in times past received unexpected acclaim. This led to me holding an exhibition, and in 2002, I was fortunate to win the landscape art competition that was part of the Penghu International Earth Art Festival.

I then began a painting depicting the historical events surrounding the Taiwanese hero Zheng Chenggong, who freed Taiwan from Dutch rule in the 17th century. The painting, which took over a year to complete, was exhibited at Koxinga Museum in Tainan and was even featured on American and Japanese TV.

In 2012, I closed down my science experiment classes and threw myself wholeheartedly into painting. The same year, I found out that the Museum of the War of Chinese People’s Resistance Against Japanese Aggression in Beijing was looking for a historical painting depicting the Battle of Baguashan. I very much wanted the opportunity to paint it especially as my great-great-grandfather had died in that battle, and I felt I had a special connection. Two years later, I was contacted by the museum and commissioned to paint the historical artwork.

A Renaissance

I immersed myself in the painting completely, to the extent that it affected my health. Given my underlying condition of hepatitis B, I was hospitalized for emergency care.

When the doctor recommended a liver transplant, I was convinced that the time had finally arrived for me to overcome the karma I inherited from my father, and I started chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo earnestly.

To minimize the risk that the liver would be rejected, the donor had to be at least 18 years of age. Fortunately, our son, who had just turned 18, qualified. Thanks to him, the surgery was a success. I recovered and completed the painting, which is currently displayed at the war museum.

A passage from The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin states: “Myo [of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo] means to revive, that is, to return to life.” I am amazed that, not only was I able to overcome illness and financial difficulty, but I am also able to pursue a creative passion and create artworks that memorialize my ancestors. My vision now is to be someone who, through art, can help build cultural bridges between Taiwan, mainland China and Japan.

Adapted from the June 4, 2021, issue of the Seikyo Shimbun, Soka Gakkai, Japan.