Healing from Genocide: Writing the Untold Stories

In April 1975, Cambodia entered one of the darkest periods in its history when the Khmer Rouge (Communist Party of Kampuchea) led by Pol Pot, seized power. Trying to take the country back to the Middle Ages, cities were emptied, and people were forced to work on communal farms in the countryside. Execution, starvation and overwork led to the death of an estimated two million people.

Here, Kong Thyda, just 15 years old at the time it began, shares her story of the genocide in Cambodia and how her Buddhist practice has helped her to heal.

For 40 years, I was haunted by voices—the sound of whippings, the screams of human misery. I tried hard to erase these memories. Now, I have come to see that they are a part of a history that must be kept alive for the sake of our future.

I was 15 years old when, on April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge, the Communist Party of Kampuchea, came to power in Cambodia.

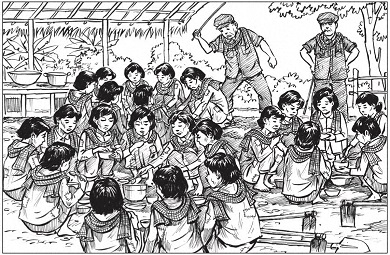

It was a time that is hard for anyone to imagine. Markets, schools and temples were suddenly closed down. Money had no value, and all personal ownership was ended. Houses, land, crops, vehicles, livestock, even jewelry—all personal property was confiscated. We were told that everything we owned needed to fit into a small bag. The Khmer Rouge divided everyone into separate groups based on age, gender and marital status, and we had to live together in these groups.

Surviving the Cambodian Genocide

My family, like others, was broken up in this way. I was part of a mobile unit that was constantly relocated from one area to another to work in the fields. We worked with hardly any rest, from morning to evening and sometimes through the night.

People died of starvation and disease. Even the fruit on the trees was seen as property of the state and couldn’t be picked and eaten without authorization. The hardest thing was the constant fear of being killed by the regime for any arbitrary reason. Anyone considered as an intellectual was put to death, as well as anyone from a wealthy family, teachers, soldiers, former government officials, people accused of being lazy or of working too hard, entertainers and those who were considered too attractive. All of these people were targets to be destroyed. It is estimated that a quarter of the population, close to 2 million people, died or were killed.

Why is this happening to me? What is life? What is the meaning of life?

In January 1979, the Khmer Rouge regime collapsed. I was 19 years old. I didn’t know if I was alive or dead. I felt dead inside.

After a long time, I was reunited with my family. However, two of my brothers had died—one of starvation and the other by suicide. I was regularly haunted by hallucinations—the fierce eyes of watchers in the trees and scenes of being whipped. I asked myself, “Why is this happening to me? What is life? What is the meaning of life?”

Finding Buddhism and Hope

One day, I was listening to a radio program, and the host talked about Nichiren Buddhism. I was fascinated to hear about the Mystic Law of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo and the idea that those who chant this phrase can draw forth their potential and attain absolute happiness in life. I contacted SGI-Cambodia and was connected with local members in 2015.

I wanted to know how I could overcome the anger and sadness of my past. I had no idea of how to do that except through practicing this Buddhism. In the Soka Gakkai, I discovered a place where people could open their hearts and talk about anything, such as the pain they had experienced in their lives, their weaknesses and their courage; a place where people respect and encourage each other with warm hearts, creating hope in their lives and building strong relationships.

I came to see that it was the human heart that caused the slaughter of so many people. So it is the human heart that needs to change. That’s when the idea to record what I experienced as a teenager during the genocide was born. And I found what it was that I could do for peace.

Turning Pain into Purpose

In Cambodia, every survivor has lost relatives or friends. But people don’t talk about it because it’s too painful.

However, when I learned that President Daisaku Ikeda had spent decades writing the novels The Human Revolution and The New Human Revolution in order to leave behind a philosophy of peace, I began to change my perspective. I felt that it was my mission to pass on the lessons of the past to future generations. I began to feel that since the Cambodian people had suffered so greatly, they should be able to contribute enormously to peace.

Documenting for the Future

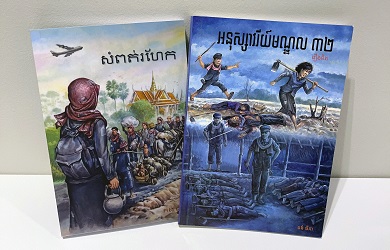

In Cambodia, there are very few books documenting personal experiences of the genocide. The transmission of this history is important, especially considering that more than half the population is under the age of 30.

Working on publishing my book brought lots of difficulties, such as having to find out the official names and locations of the detention centers, applying for publishing permission, and proofreading.

In 2018, I published my first book, Memories of Center 32, an account of my childhood during the Khmer Rouge regime and the time I spent in Center 32, a kind of prison, where I witnessed truly terrible things. After that, I wrote a second book, a novel about people rebuilding their lives after the genocide.

No Genocide Ever Again

I don’t know when I began to feel so stable psychologically, but I know it was because I was practicing this Buddhism. It requires deep and proper healing to achieve true happiness in our lives. That’s why, the Soka Gakkai is so important.

I feel like I have succeeded in changing my karma. I think about and understand things differently than before. My perspective on life has changed, and I have become a person who wants to contribute to other people’s lives, society and the world. The pain of the past has disappeared and become a lesson. The resentment has disappeared and been replaced by compassion.

I am writing for the sake of Cambodian children, and I am planning on completing a third book. I hope that war and violence will be completely eliminated in our generation. For this purpose, I will continue to write.

There is always value that can be created out of any experience. For me, that was writing. I put everything into writing so that I could play my part in preventing genocide from ever happening again.

Adapted from the May 19, 2023, issue of the Seikyo Shimbun, Soka Gakkai, Japan.